Reminiscences of the Late Mr. William Tiptaft

A FRIEND writing in reference to the Sayings of Mr. T.' which we recently published in 'Gospel Truths or Old Paths,' says, can look back to various times when his weighty and heart-searching remarks have caused much self-examination as to whether I knew anything in reality of the saving power of redeeming love; and I invariably found (perhaps you have found the same) that Mr. T.'s preaching had a great influence upon my mind. With what caution and fear have I conducted myself during the week after I have heard the good man; and how I have prayed that I might live and move in the fear of God as he did. He was the first gospel minister I ever heard for myself; and I think I shall remember to my dying day a remark which he made the first time I heard him, it was as follows: "As I was journeying yesterday I was struck by the number of trees which lined the road, and was deeply impressed by the thought that shortly my soul must live in heaven or hell as many years as there were leaves on those trees, and, as Bunyan says, Eternity at the back of them all;" he then added, "Am I prepared to die," and "How many in this chapel can say that they are ready to meet God?"' The writer adds, ' It is nearly eighteen years since I heard Mr. T. make the foregoing remark, the impression of which on my mind is so deep and lasting that I do not think it will ever wear off.' Numerous similar testimonies could be given if necessary.

We shall not easily forget his manner in the pulpit: indisputably he was in some things eccentric, but even these were the result of the labour of his soul to be faithful to his fellow-sinner. The shaking of his head and the wringing of his hands, when speaking of the fearful state of the impenitent and of the awful eternity awaiting such, gave weight to his solemn remarks and evidenced his earnestness in his work. He had a manner of repeating three times any remark which he wished to impress on the minds of his hearers, each repetition with a rising voice and with a pause between. Once, when addressing the Sunday school children, he said, I have three remarks to make to you: 1st, Be very particular what company you keep,' - a pause; and then with a rising voice, 2nd, Be very particular what company you keep,' - another pause; - and then with increased emphasis, 3rd, Be very particular what company you keep.' The effect on parents and children was great, and the advice never forgotten. In the vestry before service he would pace the room; in the pulpit during the singing before sermon he would appear in agony, without doubt arising from a sense of the solemn work before him, Unfit as he was - ignorant as he was - and unworthy as he was' (to use his own words) to stand up between the ever-living God and never-dying souls.' Earnest himself, the insincerity and the lukewarmness of money-grubbing professors of religion would make him appear sometimes very severe in his judgment of men, and he would ask, How many of you in this chapel would prefer Christ to a sack of sovereigns?' As might be expected, such honest dealing with men's souls often gave offence; and whilst the godly left the house of God praying for more grace, others left attributing his faithfulness to a bitter spirit.

Once when preaching at K., - where there was a population of some thousands of souls, but where the gospel in its purity was not preached, - he said, ' I wonder whether you could find me in this place fifteen persons who could give a good account of a work of grace in their souls.' After service the deacon asked him to take a glass of wine, he declined; he was then asked to take a glass of water, to which he consented. The deacon handing him the water, said, There, Sir, we have plenty of good water at K., if we have not fifteen good Christians.' Mr. T. replied, I never said you had not fifteen Christians among you, there may be true believers in the Church of England, also among the General Baptists, the Independents, and Wesleyans, but I doubt whether you would find among all in this place the number I have said who could give a good account of the work of grace on their souls.' The deacon was silenced.

Not only was he faithful in the pulpit, but he was equally faithful in the vestry and in the parlour; and no difference of position in the church or in the world prevented him from reproving for an inconsistency. As an instance, a minister, doubtless a good man, but light and trifling in his manner, came into the vestry after preaching and saluted him in a very jocose manner. Mr. T. approached him, and in a very solemn but gentle way, said, Friend -- does not your conscience often condemn you for your levity?' In the parlours of the rich, whom he esteemed as true believers, he has been known to ask his friends how they could indulge in such luxuries while so many poor were wanting bread. And it is said that he very rarely, if ever, omitted, when asking a blessing at meals, this prayer, Make us very mindful of the wants of others.' We know that he was mindful of their wants, and would live on the meanest fare and give away his last shilling to relieve the needy. Though supposed by many to be harsh and severe, he was really very tender in judging the state of others. A friend being very anxious to have his opinion of the religion of a certain person, took advantage of the opportunity for asking when dining with Mr. T. at the house of a mutual friend; the room in which they were sitting opened on to a lawn, - the window was open, - Mr. T., without answering the question, rose from the table, walked out of the room, and for some minutes walked in the garden, then returned, and resumed his seat at the table. The question was again put with the same result. When the question was put a third time, he said, It is very often a difficult matter to judge of one's own religion, how much harder to judge of another man's.' His company was excellent, for whenever he spoke there was something weighty; instance the following put to a friend: If you believe all you hear and tell all you know, you will not be long without enemies, but soon without friends.' Another: If you take gratified pride from your pleasures, and mortified pride from your troubles, what would be left?' Such sayings as these in company, like his pulpit sayings, led the listener to think, and the thought was profitable.

Mr. T. was truly a spiritually-minded man, his mind seemed ever occupied

by the things of God; he never appeared to weary in talking of God's

dealings; as to other matters, he seemed to know little and to care less.

One of his favourite hymns was,

Let worldly minds the world pursue, It

has no charms for me.'

He has been heard to relate how sometimes people stared at him on account

of his ignorance of passing events in the world. Once when travelling by

coach to preach, as he approached a town there was a great commotion, bells

ringing, music playing, flags flying, thousands of people thronging the

streets, triumphal arches, &c., and he asked a gentleman sitting at

his side what it all meant; his fellow-traveller, who had come many miles

to see the sight, looked at him as if he were a barbarian, not to know that

the great Duke of Wellington was to be there that day; and his indifferent

Oh indeed! ' made the man stare the more.

His zeal in preaching the

gospel was very great. A provincial newspaper, noticing once his preaching

in the market-place in a waggon during a drenching rain, remarked, The ardour

of the reverend gentleman was nothing cooled by the heavy rain which fell

throughout the service.' He used to say, Better to wear out than rust

out;' and so when out on preaching tours, which was very frequent, he

would preach three times on the Lord's Day, and often have to travel

in an open conveyance in a bleak country, fresh from a hot, overcrowded

chapel, to another place of worship for an afternoon or evening service.

Then again, he would preach nearly every evening in the week, beside anniversaries:

between services, where there was no settled minister, he would often baptize;

in which ordinance he took great delight, and in support of which his arguments

were very powerful. In addition to all this labour add that wherever he

went he found out the Lord's people (poor in this world) and visited

them, reading, praying, and speaking words of comfort at the bedside of

the sick and dying. All this labour, pursued as it was for many years without

rest, indeed did wear him out. His friends saw that it was telling upon

his health, and suggested thoughts of prudence to spare his strength; but

while he could work he would work, and even after an exhausting day he would

follow on his discourse in the vestry, and with his friends when he reached

his lodgings, with as much vigour as if he had just begun, and it was as

weighty at the end as at the beginning. He was extremely tender in his conscience,

and very fearful of any act which might lay him open to the charge of inconsistency

or want of faithfulness; as an instance of this, he was once in considerable

uneasiness of mind because he had received an invitation to attend a banquet

in connection with a society of the clergy; he took it against him that

he had the invitation, saying, If I had been faithful would they have wanted

me amongst them;' and when the friend suggested that probably it was

because they admired his consistency and faithfulness, though disliking

his views, that they thought to honour him (a Seceder from the Established

Church) with an invitation, he meekly replied, as if such a thought had

never entered his mind, Oh do you think so?' He was always very fearful

of having his portion in this life; he was frequently heard to say, What

a fearful thing to have our portion in this life;' and with much emphasis

would say,

The greatest evil we can fear

Is to possess our portion

here.'

He often said, How rich people must cling to life.' If we had everything that we could desire here, we should not want to go to heaven.' He indeed might truly say that, To live was Christ, and to die gain.' He ever expressed, A desire to depart and to be with Christ.' At length continual speaking and exposure to cold, with an almost blameable neglect of himself, resulted in an ulcerated throat with loss of voice, which for a few months preceding his death, laid him aside from his beloved work; and now that he could no longer be further useful in the Lord's vineyard, his one desire was to depart and be with Christ in heaven, whom on earth he had so faithfully served: nor was his desire refused; he was not suffered long to be silent, but was soon taken home to Sing in a nobler, sweeter song, The power of Christ to save.'

Without wishing to extol the creature, or to disparage any other good man, it may be safely said that there are but few Tiptafts; so humble, so sincere, so earnest, so self-denying, so faithful, so godly; he feared God above many. His life was most consistent, his end most blessed.

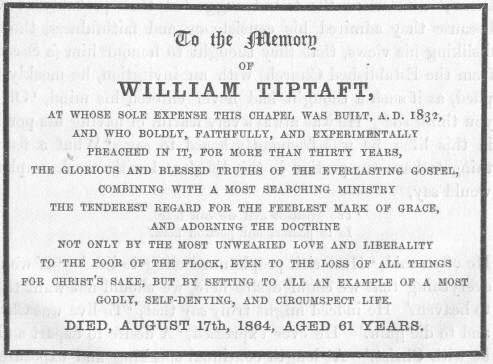

His mortal remains lie buried in the Cemetery of his own beloved Abingdon, covered by a plain stone, strictly in accordance with his simple life. In the Abbey Chapel, over the pulpit, is a neat white marble tablet with a black border, on which is the following inscription: